A glowing obituary for Sir Mota Singh

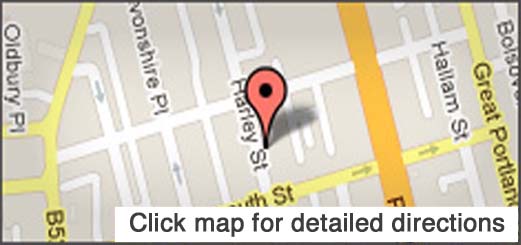

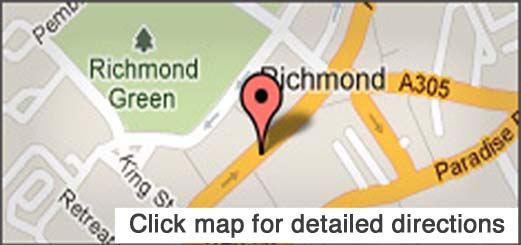

Endodontist London

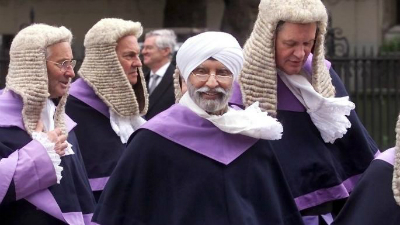

Sadly, our resident Harley Street endodontist Dr Satinder Mathru’s farther passed away last month. Our condolences are with him and his family. Here’s the obituary of the fascinating “Silver-tongued Sikh barrister who became the first judge in England for more than 300 years not to wear the traditional horse-hair wig.” Via The Times newspaper.

The starched-white turban worn by Mota Singh became the most famous in the country in 1979 when he was appointed Britain’s first judge from an ethnic minority.

Approaching the Crown Court bench in his turban, the devout Sikh was also the first judge on the English bench for some 300 years not to wear a horse-hair wig.

His appointment into the higher echelons of a profession still dominated by white former public schoolboys made headlines all over the world. He took to his new role as to the manor born. A profile on him in The Daily Telegraph remarked on his “crisply cultured voice” — the headline read: “Judge in turban typical of an English gentleman”.

In his 23 years on the bench Singh always asked God for guidance before summing up a case and won plaudits within the judiciary for judgments in a string of high-profile and complex serious fraud cases at Southwark crown court.

Outside court the diminutive native of Nairobi was an unfailingly courteous and modest figure, always dressed conservatively, often a three-piece suit, which he was remembered for wearing on hot summer days while on holiday in Spain.

He perfected the dry English sense of humour and was particularly amused by the “Jack” cartoon in the Evening Standard depicting him having dismissed a defendant who had just been found not guilty. The man in the dock says: “Thank you, M’lud, and I hope your head gets better.”

Among his many admirers was Willie Whitelaw, the home secretary, who invited him to address a fringe meeting that he was chairing at the Tory party conference in the early Eighties. Whitelaw was acutely embarrassed when someone stood up to contradict a point Singh had made before making a belittling comment about his “hat”. The home secretary asked the man to sit down and swiftly moved on to the next question, but Singh stood up, addressed the question and politely pointed out the difference between a hat and a turban. He sat down to a standing ovation.

As a young barrister in Kenya he had “never dreamt” of becoming a judge in Britain because it was a “closed shop”. One by one he opened the doors, passing his bar exams, gaining enough legal experience in Britain to be called to the Bar, finding chambers in Middle Temple and rising to become one of Britain’s foremost property barristers.

Friends and colleagues still recall the tension in 1967 when Singh appeared in court as an advocate for the first time to defend a man charged with drink-driving. It was by no means clear whether the judge would allow him to approach the bench in a turban. No objection was raised. The case, which he won, was reported in The Times under the headline: “Barrister in turban wins case.”

The pathway to becoming Britain’s first Asian judge was open and others, such as Justice Rabinder Singh, the high court judge, would follow in Singh’s stead.

Mota Matharu Singh was born into a middle-class Sikh household in Nairobi in 1930, the eldest of six children. His father, Sardar Dalip Singh, taught him how to play tabla but the boy’s greatest passion was cricket. A doughty opening batsman, he captained his school team and would later represent Kenya.

His father, who had a partnership in a motor garage in the city, was murdered when Mota was 16. He had come to the aid of an Indian woman who had been attacked. He chased the assailant down the street and was fatally stabbed. The family did not receive their father’s share in the garage business. The local Sikh community raised money for his sister to get married. The boys would have to fend for themselves.

Mota locked his tabla away, deciding to forgo his school examinations and start work to support his mother and five siblings, the youngest of whom was still a baby. His teachers at the Government Indian High School thought so highly of him that they convinced him to take his exams, clubbing together to pay his fees.

He then found work as a clerk and aged 20, at the behest of his relatives who wanted to “lift the gloom” from the family, Mota wed Swaran Kaur in an arranged marriage. It was a happy union. She survives him with their two sons and a daughter. Satinder is a dentist in Harley Street and Jaswinder runs an import-export business. Pam, who studied for a fine-arts degree, is a housewife.

Singh started to study for the Bar by correspondence course. He came to the UK in 1953 and found work at the Indian high commission while revising for his final Bar exams at night. He passed them in 1955 and returned to Nairobi to set up his own practice as an advocate. The firm became one of the most successful law practices in Nairobi, while Singh became a prominent burgher of the Kenyan capital after being elected to the city’s legislature.

Through it all he was father figure to his younger siblings, organising their education and helping them find jobs. Two of his younger brothers followed him into the law, and another became a chartered accountant.

In 1965 he emigrated to Britain with his family. To practise as a barrister he would need to find work as a lawyer. White Kenyans before him had failed to find a living in the law in Britain and told him that as an Asian with a turban he was mad to even try. After six fruitless months Singh was beginning to regret not listening to his friends. Hundreds of applications for legal positions were rejected on account of his not having any legal experience in Britain. He broke through by inventing a job for himself, persuading a group of property companies that they needed a lawyer to advise them on complaints from tenants. An early piece of legal work led to an important victory in court. His delighted employers supported him in his bid to practise at the Bar in 1967. He took up residence in chambers at 1 Mitre Court in Middle Temple and over the next decade established a reputation as one of Britain’s leading “landlord and tenant” barristers, often mentioned in legal dispatches as the “silver-tongued Sikh barrister”.

Singh’s profile was raised in 1968 when he was appointed as one of 12 members of the Race Relations Board to advise the director of public prosecutions on alleged breaches of recent legislation to outlaw discrimination on the “grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins”.

He took silk in 1978 and a year later the lord chancellor appointed him as a recorder. He proved his mettle and became a full-time crown court judge in 1982, where he tried cases at Southwark crown court.

In February 1995 he heard the case of Michael Ward, a former merchant banker with SG Warburg and chief executive of European Leisure, who was convicted of rigging the stock market before the company’s takeover of Midsummer Leisure.

Singh was a kind mentor to aspiring barristers. One young Sikh who was training for the Bar once came into his office to say goodbye; he was giving up because he could not afford the fees. Singh wrote him a cheque. Reinvigorated by the belief that Singh had shown in him, the young man found a way to meet the costs and framed the cheque.

Faith came first. At home in Wimbledon Singh recited the night prayer Kirtain Sohela before going to bed; he would awake in the middle of the night to bathe and then recite the Japji Sahib.

The teetotal vegetarian remained an active member of the Southfields gurdawara for 45 years but realised that the institution needed a new more democratic code of governance. He commissioned, under his guidance, a new constitution, which is now in place. The document was subsequently adopted by other gurdwaras.

Singh rose to become deputy presiding judge at Southwark crown court before his retirement from the bench in 2002. On his last day more than 100 judges, including law lords and Court of Appeal judges were in attendance. Lord Woolf, the lord chief justice, delivered the valediction, praising Singh’s “magnificent contribution to the administration of justice in this country”. The court commissioned a portrait of Singh in his robes that hangs in the judges’ dining room.

In retirement he was at his desk in shirt and tie by 9am, often writing speeches for conferences and functions, for which he was much in demand as a speaker. One sanctuary of unadulterated relaxation was the members’ enclosure at Lord’s cricket ground.

Several years after Singh hung up his gown, a buff-coloured envelope marked “Cabinet Office” dropped on his doorstep. He opened it with trepidation, racking his brains for a possible official misdemeanour in his past that had come back to haunt him. He was amazed to find that he was to become the first Sikh to be knighted for “services to the judiciary and charitable causes”.

Singh said he was proud to live in “one of the few countries in the West that recognised immediately that it was essential for a Sikh to wear the articles of his faith”. It dismayed him that religious symbols were increasingly proscribed in public places. In 2010 he was interviewed by the BBC, criticising the decision of a school to exclude a Sikh boy who refused to remove his Kirpan, the ceremonial dagger that is one of the five articles of faith.

He lamented the disintegration of faith in modern society and especially the “pernicious practices” that had crept into Sikhism. He was a gentle mentor to young Sikhs, however “wayward”. For someone who had spent his professional life being paid to pass judgment on others, he was remarkably unjudgmental.

Sir Mota Singh, QC, Crown Court judge, was born on July 26, 1930. He died on November 13, 2016, aged 86

Endodontist London

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/Endocare/

Twitter : https://twitter.com/EndoCareDentist